It's the Beginning of Year Three, and Truthfully...

Despite the summer heat that just won't loosen its grip on Kansas, we're technically heading into fall. School has been underway since mid-August and I'm thankful to have established some sense of routine as a public school librarian. Could there possibly be room for more sunshine, rainbows, and understanding regarding the library program that should be in place for students, teachers, and staff? Yes, oh yes. Am I spending every weekend at work cleaning, selecting, straightening, repairing, rearranging, cataloging, in-processing, researching, and reading? No, definitely not.

Being in year three of my librarianship rather than years one or two has greatly contributed to a better balance between my work and personal lives, but so has purposeful decision-making on my part. I deleted my work email from my phone. I leave my work laptop in my office as often as I can. When I walk to my vehicle and drive off of school property, I'm done with my profession/career for the day. Well... until I spy a new book that I know readers will enjoy, or I receive a box of books to review for KNEA's Reading Circle. Books are my thing, but so is yarn. And antiquing. And baking.

My fellow librarians and I have realized that our building administrators are for the most part still getting used to their new jobs, too. None have been here long enough to remember what the district's prior iterations of our library programs looked like, felt like, or operated like. It's possible that they've been told "it's always been done this way," which is a shame since they haven't asked any of us to verify whether or not the statement is true. It isn't. Of course, with so many other public schools operating without full-time librarians or library assistants, or being shuttered completely, there's a good chance that our building administrators simply feel lucky to have libraries available to offer classroom teacher prep times and librarians able to fulfill the requirements of grant funding and response to interventions, and, oh, to also teach all students, manage the library's collection, repair items, raise funds to provide a purchasing budget, promote reading, help students discover not only the joy of reading but of self-selected content, and support curriculum and testing requirements through collaboration with grade levels and individual teachers.

Unlike year one when I donated fourteen unpaid days of my summer vacation and thousands of dollars from my own bank account to get the library organized, freshened up, and into a manageable, functioning appendage of some of our school's most valuable and important resources (combined with early-morning arrivals and weekend visits), this year I'm able to manage most must-dos by arriving an hour and a half before my contracted time each morning. Are there enough contract hours in the day for me to have the library up and running efficiently and effectively without having to beg for volunteers or wrangling students into doing some of the more routine tasks? Absolutely. Do I get all of those hours? Absolutely not.

You see, sixteen years ago, when I arrived in the district, the school libraries each had a certified librarian (master's degree) and a librarian's assistant. The assistant was trained by the librarian to handle minor book repairs, help students and teachers with finding books and materials, scan books in and out, shelve books, straighten stacks, give overdue notices to students, and other tasks as needed, such as in-processing materials (adding spine labels, colored stickers, barcodes), delivering books to classrooms, and helping with book fair volunteer management. While the librarian could also take care of those tasks, they were usually busy with library instruction. Selecting books (by having the time to actually read them first) for read-aloud content, watching, evaluating and selecting other media resources, creating lessons and preparing materials for activities, as well as teaching and reteaching students and staff about organizational systems, research, information accuracy, mis-and-disinformation, took up a lot of time. So did collaboration with teachers as they expanded content from their classrooms into the library and team-taught to help students.

Ebbs and flows in funding impact our district every year, and we've built two brand new schools and expanded the board office in the time that I've been here. Library assistant positions were cut shortly after those staff members had been pulled from the library to help in the cafeteria, during arrival and dismissal duties, etc. Librarians were encouraged to ask for parent volunteers to take up the slack, which they did, because h-e-l-l-o, they were still teaching full-time, evaluating resources, maintaining and updating the collection, and all other things required to keep a library ship-shape for patrons. Retirements happened. New hires discovered that they too, would need to depend upon parent volunteers and help from sixth-grade students to keep books on shelves, and they'd only receive funding for new books, repair supplies and cataloging materials if they held book fairs, unless new curriculum was being adopted. Librarians began being pulled from the libraries during times when they didn't have students in order to "support" student interventions happening elsewhere in the building. If volunteers were unavailable, books didn't get shelved, repaired, checked out, checked in, weeded, or replaced.

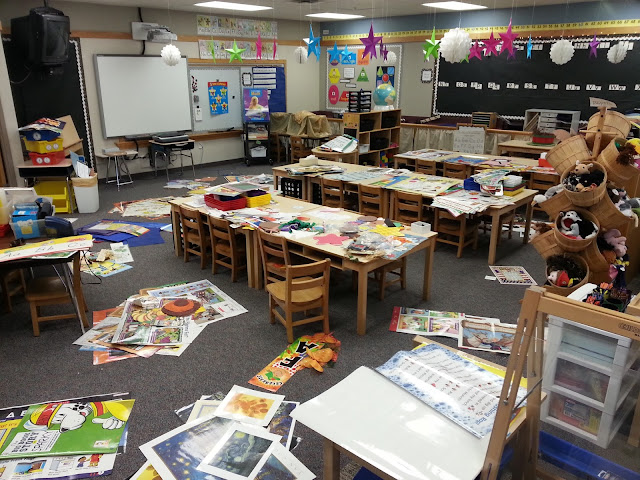

The collection wasn't updated. New, more accurate resources weren't made available to students. Periodicals from the 1980s were reused as subscriptions lapsed, encyclopedias grew outdated and continued to take up substantial amounts of space, and ebooks were purchased so students could be taught to use and read them as much as possible. Ratty, outdated books remained on shelves. New hires sought work elsewhere, moving to districts where they were told they would be able to work as full-time librarians. Then the pandemic hit, and our libraries were shuttered and librarians and other specialists remained employed, but worked as classroom aides, remote learning teachers, and interventionists. No library books were checked out for a year. Dust collected, mice invaded, mold grew between pages, everyone hunkered down, and the library hibernated, likely coming close to death. And then I was hired.

Having classroom and remote learning experience, a keen interest in digital media, and a love of books, reading, and sharing, becoming my school's librarian was a great fit, and I had my work cut out for me. Gone were the days when assistants and volunteers were available. I was solo. I had to be in at least two places at once during instruction, checking in and cleaning books, while also reading books to students. Creating read-aloud videos was how I spent many of my weekends that first year. I'd play the video and clean and sort books on carts near the students, who were still in cohorts because of pandemic protocols. Scents of hand sanitizer and Lysol wipes filled the air. Books had to be quarantined, and I was able to get one, yes one, parent volunteer to come in once a week to reshelve books after they'd been sitting for four days. She caught COVID right after Christmas, and didn't return. I spent so many hours of my own time frantically trying to not only learn my job (I wasn't trained), but to do it away from the library as specialists were again pulled during "down" time to help elsewhere in the building (who in their right mind thought librarians were sitting around eating bonbons and watching soap operas when students weren't visiting?). I would not be reimbursed for my purchases, even for those items directly related to book repair. I purchased most new books out of my own paycheck as we couldn't host an in-person book fair to raise money. I accepted donated books from families and staff members. I had to give up half of my prep time daily in order to provide "open" library for speedy readers, students who had missed their class library visit, or students and staff who needed research and instructional resources. Year one was rough.

I got some breathing room in year two, and had flexibility in having a prep time that was helpful for me and the needs of the library, while also still being able to provide an extra "open" library spot for speedy readers and others each afternoon. I had to provide academic interventions elsewhere daily, so coming in to work an hour and a half early each morning provided me the time to repair books, read, shelve, create book displays, and handle book requests. We were able to have our first in-person book fairs since the start of the pandemic, and families were thrilled to be able to select wonderful books and literacy resources for their children. Many incredible parents volunteered their time to keep everyone on schedule and supported, and the money we raised made it possible for me to fund book purchases and other items necessary for collection maintenance and reading promotion. Last year was also when I realized that having spent thousands of dollars to earn my master's degree and working practicum hours to obtain the knowledge and expertise necessary to fulfill not only the roles of licensed librarian AND library assistant, I was VERY reluctant to "just train some volunteers." I'll ask for library volunteers to do my job when the principal, nurse, kitchen manager, custodians, and superintendent put a call out for volunteers to drop in any time to do theirs, thank you very much.

Administrators seem to have spent part of last summer deciding that one-size-fits-all: every schedule must be the same, every specialist must be available for duties outside of their instructional locations, and librarians' time is better spent monitoring students using exergame equipment for behavior and learning interventions and pulling small groups of students outside of class for academic interventions, rather than providing for all learners in the building by allowing us to do the work that historically required (and continues to require) two people (or many volunteers) on a full-time schedule to get done daily in order to effectively maintain the library's resources, plan and teach. I had to advocate for speedy readers/absent students again, perhaps because no librarian was invited to sit in on the schedule planning over the summer. I continue to have to read books and create read-aloud content on my own time, unpaid. Most days I am at work an hour to an hour and a half before other staff arrive. My lessons and read-alouds don't last more than fifteen or twenty minutes, and I have implemented STEM and literacy centers to help keep students busy and on-task while I help those who need me to navigate the collection with one-on-one guidance. I shelve books during the read-aloud video or centers. Making sure I touch on every essential library standard isn't the same as guiding students to mastery of them, but having time to provide library interventions isn't considered important, even for ESOL international students from different countries. I have prep time at the end of the day when I'm exhausted. Teachers still try to send students to me during my prep because that's the best time for their students to come to the library, before dismissal. My fellow librarians and I are only able to meet once a month, and we have big projects that are essential to the quality of our library programs, student advocacy, and instructional support that we need time to complete. The beginning of year three might not be the train wreck of year one, but it definitely has not been conducive to facilitating an effective library program that supports all learners.

Sure, students and teachers could wait a month or so for a book to be repaired when a librarian is in the building during parent-teacher conferences and isn't needed elsewhere... but should they have to? Books requested by readers could remain uncataloged, not processed, and unavailable until the librarian has the time to sit and do data entry (called "cataloging"), labeling, stickering, stamping, and displaying, months later... but should there be a backlog of items, and do such delays really support readers? I could spend my evenings and weekends reading as many books as I can in our collection in order to improve my content knowledge for book recommendations, collection analysis, and lesson planning, but should I have to? I'd rather attend my son's football games, go out to eat with my husband, plan my handmade gift items for the holidays, walk my dog, get chores around the house done, or frankly anything else other than doing unpaid work or having my personal time consumed by thoughts and resentment about how effectively I could be doing my job if only I would be given the time to do so. Grants should include funding for the hiring of full-time support staff. Chipping away at the efficacy of library programs doesn't guarantee the success of academic interventions, but it does ensure that all patrons, students, and staff, get less of what they need and are supposed to get according to our state department of education. Robbing Peter to pay Paul isn't a great strategy. I could do the bare minimum: never create book displays; never clean books; never create student content or select and provide STEM materials for students; weed (throw away) damaged books rather than repair them; let crap accumulate in the professional library; not create book sets, digital libraries, or resource lists (unasked) for teachers; never shelf read or inventory to try to find "lost" books that were misshelved... the list goes on and on. But I didn't become a school librarian to do as little as possible: I became a librarian to do it ALL.

What do I know at the beginning of year three? I know it's possible to be one librarian doing the full-time work of two people in a single building as long as instruction isn't my sole focus. As for one librarian having to be a full-time educator, collection manager, and academic/behavior interventionist? I know that no, things have not always been this way, and no, they don't work effectively this way, and no, they shouldn't be expected to "work" this way.

Comments

Post a Comment