Curriculum Redesign

Having taught kindergarten for over twenty years in Alaska, New Mexico and Kansas, my career has been full of mandated, self-driven, and even accidental professional development and reflection. I've attended inservices, trainings, seminars, and consortiums, have taken graduate level courses to keep abreast of trends and best practices (and maintain my certification- employment is a good thing), and have participated in my fair share of curriculum evaluation and adoption meetings. I've been fortunate to be a kindergarten teacher for such a long time, and that the truths of four, five and six-year-olds from 1994 are still the truths of young children today. As a parent of two college graduates and one middle-schooler, I can attest to the range of school experiences that exists between my eldest and youngest children, and recognize that their learning and living tools have evolved just like mine and my mother's did.

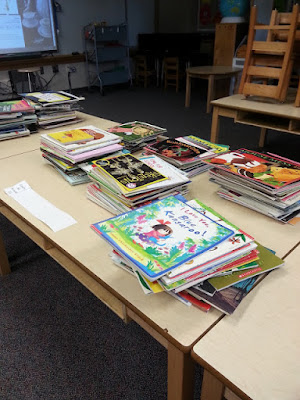

I've shuffled my own professional and classroom libraries seven times, weeding out unused or obsolete content (never fear, Very Hungry Caterpillar, Clifford, and Max, for you are collection-worthy FOREVER), and have made room for new additions (welcome to kindergarten, Pete, Captain Underpants, and any book by Jon Klassen). I've been the teacher who used solely the consumables provided by the district with crafty activities suggested by The Mailbox, who then gradually morphed into a loyal buyer of language arts, math and science packs and books aligned with the curriculum. I now exist in my current state as an occasional content creator who shares work pages and activity ideas with grade level colleagues within my district, and some of my ELA and Math content packs are for sale to the public. I've been a teacher long enough to know with certainty that everything changes and that this evolution does not always require throwing the baby out with the bathwater. When redesigning curriculum, we can be flexible, honest, critical, and innovative.

Many schools and districts experienced awkward growing pains that resulted from No Child Left Behind, and when state standards became clearly articulated and the Common Core was first implemented, my fear was that they would be misinterpreted as advocacy of a one-size-fits-all framework and structure within which very diverse, organic and dynamic learners and teachers would be stuffed and forced to perform in very narrow ways (focused on standardized assessments), with a limited curriculum paced inflexibly between deadlines for mastery. Regarding curriculum delivery, I have encountered administrators who expect four kindergarten teachers to be reading from the same page in the teacher's manual during thirty-minute long "sit down" lessons that begin and end at exactly the same minute, and I have worked with new-to-service colleagues who believe that iPads and touchscreens that encourage the use of single-finger navigation are just as beneficial (if not more so) than taking the time to develop a child's grasp through the use of pencils, crayons, markers and paintbrushes, as tablets are much less messy and "don't waste paper." "We won't need room for a library in the near future, because everything will be digital, and students will be able to Google everything," is another assertion I've encountered. Occasionally, suggestions I've made to other veteran teachers about modifications to our instruction and curriculum have been considered an affront: they want to teach the exact same content in the exact same way for the duration of their careers. They refuse to acknowledge or consider the possibility that education might need to evolve, be reformed, or, according to Sir Ken Robinson, revolutionized:

The range of focus for our teacher evaluations affects curriculum delivery as well: new teachers have more unannounced pop-in visits that cover classroom management and must therefore rely heavily upon grade level colleagues for help with curriculum-specific needs, while more experienced teachers (whose students aren't rabble-rousers) can schedule two observations for the entire year with an obligatory five-minute pop-in, the resulting administrative comments and suggestions focused on actual instruction and the delivery of curricular content. Most PLC and planning meetings address the performance data of students, not the curriculum content itself.

Most of the education reforms regarding curriculum I've observed over the course of my career have focused on the replacement of content delivery tools that we put in students' hands, such as the iPad vs. pencils situation I mentioned earlier, the trade-off scenario over whether or not schools should drop penmanship/cursive handwriting for keyboarding, or the disparity between those teachers who allow students to utilize their own handheld devices for learning and those who confiscate phones at the beginning of every class. Canned programs and mandates, scripted instruction, outdated content, excessive focus on new tech tools and the desire to resemble assembly-line efficiency in instruction and learning are distracting factors that continue to prevent the necessary evolution of actual curricular content for 21st-century learning. Budgets that can't support local curricular content (Alaskan students are offered not only French, Spanish or Japanese language courses but classes for indigenous languages such as Inupiaq or Dene/Athabaskan for example) further limit a district's ability to meet the diverse needs of its students. From school boards and administrators to those classic hoarders, veteran teachers, the need is strong to weed through piles and boxes of curriculum materials, and view every item through the lens of asking "does this work for my students NOW the way it worked for me or my former students THEN?" If the answer is "no," OUT IT SHOULD GO.

Every year, we learn more about the development of children that can help us better judge, select, create, and grow curriculum. Students today still want to learn and seek out content on their own even when they're away from school, a natural inclination that hasn't changed over time. Students should be able to be guided through content and tasks that will be relevant to their day-to-day living and help them develop necessary foundational skills that will support their ongoing learning through elementary, middle, high school, and higher learning opportunities. The following questions still remain as I continue to ponder the need for redesigning curriculum:

How do we develop in teachers the intrinsic motivation to seek out high quality, relevant content (instead of blindly accepting curriculum kits) and deliver it in ways that students find enjoyable, relatable, and beneficial?

At the end of last year, administrators and curriculum instructional specialists in my district hand-delivered boxes to each classroom so that teachers would place all outdated Math and ELA curriculum materials into them, and removed them from every building by a set date so we'd have room to receive and store the new kits. Our new ELA curriculum materials were selected by teachers representative of different grade levels.

Having experienced buyer's remorse, how can districts hold publishing companies and content creators accountable to provide accurate and appropriate curriculum resources?

Our last math adoption committee didn't review consumable materials for every grade. As a result, the kindergarten workbooks contain over eight-hundred pages with only a third of them able to be used independently by students as practice or reinforcement. The amount of waste is incredible.

Where does the thread of curricular content essentials start for any given subject and how can we weave those resources and references together with other strands so that students can connect their learning instead of isolating their strategies and ideas?

I have found the Kansas Curricular Standards for Library/Information and Technology document extremely helpful for my graduate studies, and am looking forward to sharing it with my colleagues in the future.

And to echo Sir Ken, how far must we speculate into the future, trying to predict the content our students might need? Should we, in fact, focus more on helping our students to develop their problem-solving, research, and innovative skills?

I have found the Kansas Curricular Standards for Library/Information and Technology document extremely helpful for my graduate studies, and am looking forward to sharing it with my colleagues in the future.

And to echo Sir Ken, how far must we speculate into the future, trying to predict the content our students might need? Should we, in fact, focus more on helping our students to develop their problem-solving, research, and innovative skills?

Comments

Post a Comment